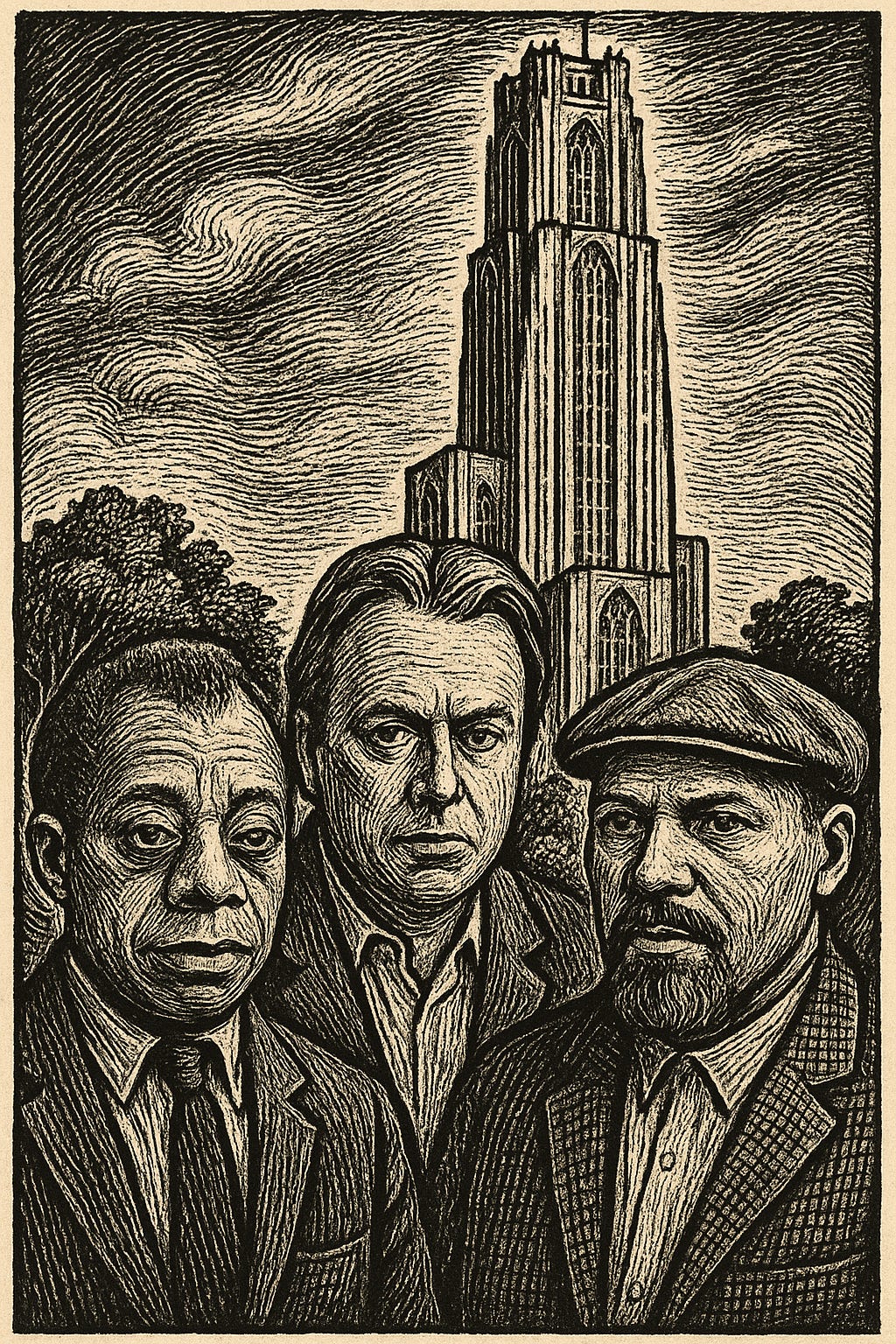

James Baldwin, August Wilson in Pittsburgh

The Blue Vote and Why Allegheny County Remains Blue for 100 years

The Prophets of the Hill: Baldwin, Wilson, and the Pittsburgh Renaissance

By Carl Cimini

If you can make it in New York, you can make it anywhere, said so often, but what happens if you try to make it in a provincial town where workers’ history is that of blood and land salted by corporations for a century?

Artists, writers, and creatives lived, visited, and labored in this land—a tundra-like expanse that feels pulled from a Tarkovsky film. Formed during the Ice Age, this ravined plateau was never meant for farming. But its rivers became conduits of industry, carrying minerals that would forge the bones of American cities. Beneath the soil, coal lay buried—extracted at great peril to fire the steel that girded the nation from coast to coast.

This was not just a place of labor—it was a crucible where life, death, and truth fused. Here, generations risked everything to build the physical and spiritual infrastructure of the 20th century. It became a kind of laboratory: a site of struggle, learning, and revelation for people who lived a century beneath the boot heel of elite power.

And from the close of the 19th century onward, three men would emerge from this darkness—teachers, writers, prophets—speaking truth to the exploited. From this unlikely terrain, they found a backdoor to global renown.

Pittsburgh, long dismissed as a smoke-stained husk of industry, harbors ghosts—prophets, really—whose voices still echo through the alleyways of the Hill District. This isn’t just a story of rust and rebirth; it’s a gospel of artistic defiance. And at the pulpit? James Baldwin and August Wilson, two men who never lived in Pittsburgh at the same time, yet whose spirits collided there like steel on steel.

And in the shadows of that pulpit—smoking, biting, brilliant—sits Christopher Hitchens. More on him shortly

.

James Baldwin Comes to the Mountain

In 1955, a young James Baldwin—fresh off the publication of Go Tell It on the Mountain—traveled not to Harlem or Paris, but to Pittsburgh. It was here, at the University of Pittsburgh’s Stephen Foster Memorial Theater, that The Amen Corner premiered.

Yes, Baldwin's first play saw light not under Broadway’s glittering marquees, but beneath the dim glow of a mid-century steel town’s intellectual avant-garde. Pittsburgh’s Black communities, especially in the Hill District, saw their lives mirrored in Baldwin’s vision: the reverent music of the storefront church, the tightrope between piety and protest, the domestic heartbreaks buried under centuries of systemic rot.

Pittsburgh didn’t just host Baldwin—it understood him.

August Wilson’s Hill, Baldwin’s Echo

Enter: August Wilson. A native son of Pittsburgh’s Hill District, Wilson was Baldwin’s spiritual heir. If Baldwin gave us the lyrical rage of Harlem’s exile, Wilson gave us the blue-collar poetry of Black Pittsburgh. Together, they mapped the emotional cartography of the Black experience—one with a zip code in pain and a postal service of grace.

Wilson called Baldwin “the greatest essayist in the English language.” But more than that, he absorbed Baldwin’s deepest lesson: that art, when done right, is dangerous. It exposes the nation’s lies and dignifies the souls it has tried to crush.

Where Baldwin said, “The place in which I’ll fit will not exist until I make it,” Wilson answered: “Fine. I’ll build ten of them. One for each decade.” And so he wrote his ten-play Pittsburgh Cycle, placing the Hill District on the map of American consciousness with a thunderclap.

The Atheist in the Choir: Christopher Hitchens and the Fire of Language

But the lineage of Baldwin didn’t end with Wilson. It stretched into unexpected places—even across the Atlantic, and back again to the steel-bound lecture halls of Pittsburgh.

In 1997, Christopher Hitchens, the British-born polemicist, atheist, and fire-breather, served as a visiting professor at the University of Pittsburgh. There, he taught literature and journalism, infusing young minds with the same blend of erudition and defiance that Baldwin once embodied. Different in tone, but aligned in purpose.

What did Baldwin and Hitchens share?

A deep belief that words are weapons.

A willingness to stand outside the tribe—even at the cost of exile.

An unflinching gaze turned toward empire, hypocrisy, and faith, wielded with intellectual ferocity.

Where Baldwin sermonized from the margins of Black America, Hitchens roared from the halls of Oxford and C-SPAN. Yet both were public moralists, committed to a truth that didn’t need to be palatable to be powerful.

Imagine, for a moment, Baldwin’s gospel cadence answering Hitchens’s British bark, both echoing down the corridors of Pitt—a university that, by some twist of fate or cosmic logic, gave platform to them both.

Renaissance, Interrupted and Reignited

Today, the ghosts of Baldwin, Wilson, and even Hitchens whisper in the ears of new generations: playwrights like Bria Walker, poets like Cameron Barnett, and institutions like City of Asylum, BOOM Concepts, and the August Wilson African American Cultural Center, which now anchors the creative soul of the city.

Outside Pittsburgh, the renaissance is national. Movements like Black Lives Matter, prison abolition, and the push for artistic equity channel Baldwin’s fury, Wilson’s stagecraft, and Hitchens’s unrelenting skepticism.

Their words animate TikToks, town halls, and tenured lectures alike. Their spirit says: We are not here to entertain you. We are here to indict you—and to uplift ourselves in the same breath.

The Furnace Still Burns

Pittsburgh is no longer just the city of steel; it is a city of fire—intellectual fire, cultural fire, prophetic fire. Baldwin lit a match there in 1955. Wilson kept it burning through the Reagan years. Hitchens stoked it with his cigarette-stained syllables in the ’90s. And today, that fire passes to those who see the stage as a sanctuary and the street as a set.

Let no one say Pittsburgh is forgotten. It remembers. It resists. And it reinvents. If you need to test your craft, come to Pittsburgh, you’ll work and develop your art, it won’t make you the next Mr. Rodgers but it may make you the next George Benson, Andy Warhol, or Billy Porter.

“You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.”

— James Baldwin“Confront the dark parts of yourself, and work to banish them with illumination and forgiveness.”

— August Wilson“The essence of the independent mind lies not in what it thinks, but in how it thinks.”

— Christopher Hitchens